This blog post is a bit different from all the others. The subject is Cris Tovani’s book Do I really have to teach reading?, the set text book for the postgraduate students doing my unit ‘Literacy across the curriculum’. The course begins in a couple of weeks.

For the past three days I’ve set aside the mornings to read the book, armed with my sticky labels and highlighter pens. After reading each chapter, I’ve been writing up some thoughts. I’ve decided to publish these in this blog partly as a guide for any of my students not sure how to approach reflective journal writing, and partly in the hope that this post might help make some connections with teachers who have also used some of Tovani’s ideas.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Half an hour ago I picked up our textbook for the first time. Tovani’s Do I really have to teach reading? I’d heard good things about it, but still had a lingering worries.

- Is this going to be one of those trite books on ‘How-to-achieve-instant-success-in-10-easy-steps’?

- What kind of classroom experience has this author had? Or does she sit in some ivory tower?

- Is her focus going to be exclusively on reading, on the act of decoding words on a page, or is she interested in the broader (and more important) question of how we learn, through various disciplines, about the world?

- How might what she says align with what I’ve discovered about Josh?

- How might what she says align with the seven propositions that I’ve come up with? Will I end up amending my list?

The first chapter (‘I’m the stupid lady from Denver’) answered some of these questions. She seemed both down-to-earth and thoughtful at the same time. Experienced but open to new thoughts in the light of further (sometime uncomfortable) experience.

Two things stood out for me.

The first was her insistence that good questions were the key to reading success. We need to begin to read with questions in our mind which we hope the text will answer, and I noticed how true this was of the way I was reading her book. I had questions which I wanted answered. And not just any question. As Tovani says (p3), ‘the questions have to be questions that I really care about. I can’t ask any old question – it has to be one that I truly am curious about’.

I wondered, as I read this, how many of the postgraduate students would be coming to this course on literacy across the curriculum with a sense that it was going to answer questions that they really cared about. I wondered what I might do, in the first week, to help them discover some of these questions.

I also liked her focus on the broader issues of learning. We want our students to learn what our subject has to teach them, and reading is a means to that end, not the end in itself.

We are simply trying to help kids get the skills they need to understand and learn about the content we as teachers care passionately about…” (p7)

Meaning doesn’t arrive because we have highlighted text or used sticky notes or written the right words on a comprehension worksheet. Meaning arrives because we are purposefully engaged in thinking while we read. (p9)

“Purposefully engaging in thinking…” Isn’t this education in a nutshell? Isn’t this the sole aim of this university unit? Of every classroom? To the extent that our students are ‘purposefully engaged in thinking’ (instead of ‘skillfully engaged in avoiding’, or ‘skillfully engaged in ticking the right boxes’), our job as teachers is pretty much done. How we get to them to that state, or how we organize our classroom so that this kind of purposeful thinking flourishes, is a very complex matter. But that’s the goal.

Chapter 2 The ‘So What?’ of reading instruction

Again, a great little chapter which again keeps the focus on the ultimate purpose of what we do. Hence the question: ‘So what?’ As I was reading it, I kept thinking about stimulus questions for my postgraduate students, or ways I might help them reflect on Tovani’s ideas. But then I read this:

Good readers don’t need end-of-the-chapter questions or isolated skill sheets. They ask their own questions, based upon their need for a deeper understanding of specific aspects of the text. (p20)

So maybe the only question I need to ask my students from this chapter is: So what?

***

I’ve just got back from a walk on the beach (it’s school holiday time), and when I walked back in the front door I saw Tovani’s book sitting on the dining room table where I’d left it after reading the first couple of chapters this morning. As soon as I saw it, I wanted to pick it up and read Chapter 3. Yet the book has been sitting on my desk at home for the best part of a month, untouched. Up until today, I haven’t been motivated to read it.

What’s changed?

Is it just that I’ve forced myself to read the first chapter and have found that I’ve enjoyed it? I don’t think so. I think it’s more than that. And I think the ‘more’ is relevant to this whole topic of literacy across the curriculum.

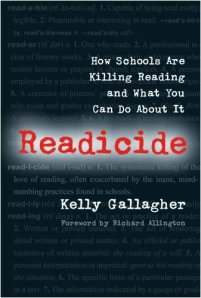

Over the past couple of months I’ve given myself time to prepare myself for the content of this course. I’ve wondered about the question of relevance: is the teaching of literacy really the business of all secondary teachers, regardless of their discipline? I’ve written down some initial thoughts in my blog, and had a go at formulating some maxims or propositions. I’ve argued over the content of the course and I’ve written a unit plan. I’ve spent some time talking to Josh, a secondary student at the school where I teach, and I’ve mulled over what he’s told me. With a group of other teachers I’ve read a book (Readicide, by Kelly Gallagher) on how schools are systematically killing off students’ motivation to read.

So I’ve come to the reading of Tovani’s book in a very active and purposeful frame of mind. I’ve done a lot of thinking about the issues before I’ve opened a page.

How differently we often approach things at school. I visited a class the other day where, as an introductory exercise to the study of a Shakespeare play, the class was asked to read a number of articles about Elizabethan England and Shakespearean theatre. No warm up. No preparation. No pre-thinking. No eliciting of questions. Just straight into the reading, cold. Result? Little engagement, little interest and no useful learning.

My postgraduate students won’t have had the time to prepare for this course in the same way I have. But nor will they then come to it cold, like the students in the Shakespeare class. Their desire to become good teachers will most likely mean that they’ll read the Tovani book in the spirit she advocates: ‘purposefully engaged in thinking while we read’?

Tovani Chapter 3: Parallel experiences

If you were going to plonk every teacher on a spectrum with those who see the big picture (the thinkers) at one end and those who see the detail (the doers) at the other, then I’m with the thinkers. I’m stronger, therefore, with ends than I am with means.

Tovani seems to have a nice balance, and I’m guessing what I’ve got to learn from her is more to do with means than ends. Someone at the other end of the spectrum, the doer, is perhaps more likely to learn from what she says about the big picture.

In this chapter she makes the following point (p35):

If you’re able to slow your thinking down a little and notice things that you do when you read content material, you can teach the strategies you use to students.

Here’s a challenge for me! Next term I’m teaching Romeo and Juliet to my Year 10 classes. I tend to focus on the big picture: on what the play says about love and hate, for example. We spend a little bit of time getting the basic plot and the main characters clear, and then we make connections between the drama in Verona and what’s happening in the students’ own lives. We revel in the Baz Luhrmann film (or at least I do!). I also focus on the sound of the language and the drama of the scenes, so we get out of our seats a lot and act out parts.

But do I do enough to help the students read the play? I don’t mean that I should be encouraging them all to sit down and read Romeo and Juliet from cover to cover. I’ve never done that, and I’m sure it would kill the thing stone cold dead if I did. I’m thinking more about how they might make sense of a difficult passage. How they might work out what it’s about, and how it’s saying what it’s saying? (And, by extension, how might they make sense of any difficult passage, not just in Shakespeare but in any challenging text they come across in their English studies.)

I’m thinking of Josh here. He was in my class last year when we studied Macbeth. I suspect that much of it went over his head, or that he relied on SparkNotes. Could I do it differently this year?

Here’s an experiment.

I’ve just found a passage in Romeo and Juliet that I don’t remember reading before. (I probably have, but I’m 62 and I forget things!) Here it is:

Indeed I never shall be satisfied

With Romeo till I behold him – dead –

Is my poor heart so for a kinsman vexed.

Madam, if you could find out but a man

To bear a poison, I would temper it

That Romeo should upon receipt thereof

Soon sleep in quiet.

I then went into my 15 year old son’s room and asked him to read it. He saw the film some years ago and knows the basic plot, but he doesn’t like reading Shakespeare.

When he’d finished reading this short passage, he said “Well, at least I get this bit. This guy wants Romeo dead.”

“Who does?” I asked.

Oliver looked down at the text and this time noticed something he hadn’t taken in first time.

“What? Juliet? Why would she want Romeo dead? Or maybe I didn’t get it? Maybe Juliet can’t stand being in love with him and wants him dead?”

I could have said, “You’re not sure you got it right?”, as Ol was now doing what Cris Tovani advocates, letting his questions guide his reading. But because I wanted instead to do my own slow reading of this passage, and to notice how I went about making sense of it, I left it there.

How did I make sense of it?

I didn’t understand what ‘tempering’ the poison meant, but (like Oliver) I got the gist of what she was saying. The line

Is my poor heart so for a kinsman vexed

didn’t seem to make grammatical sense until I reminded myself that Shakespeare (and poets) often muck around with the order of words, and that the line might have been easier to read had it been:

my poor heart is so vexed for a kinsman

Same words, different order. Now it made perfect sense, though this time we’d lost the steady beat of the iambic pentameter.

Like Oliver, I was initially surprised to hear Juliet wishing Romeo dead, and offering to administer the poison herself. Why was she saying these things? It didn’t seem to make sense.

I looked to see who Juliet was talking to. It was her mother, and I knew that Lady Capulet knew nothing of Juliet’s marriage to Romeo. Was Juliet dissembling? I flicked back a couple of pages to find out when this conversation took place. Romeo has killed Tybalt (her kinsman), Juliet knows what has happened and has just said goodbye to Romeo after a secret overnight visit to her bedroom, and Lady Capulet has found Juliet with tears on her face. Juliet has to explain her tears, so she pretends to be weeping for Tybalt, and Lady Capulet puts into Juliet’s mind the idea of revenge through poisoning. She says to Juliet:

I’ll send for one in Mantua,

Where that same banished runagate doth live,

Shall give him such an unaccustomed dram

That he shall soon keep Tybalt company;

And then I hope thou wilt be satisfied.

Yes, it all made sense now. Juliet was dissembling.

Tovani says that if we can uncover our own strategies and teach these to our students, they too will read better. How did I make sense of this passage? By reading it slowly and using my knowledge of the way poets play around with word order for the sake of rhythm. And by letting my questions guide my further inquiry. (Why is Juliet saying these things? Who is she talking to? What’s just happened? Is she dissembling?)

I’m guessing that if I were to show Oliver how I went about doing this, he might have another string to his interpretive bow when he next encounters a confusing passage in Shakespeare.

Did I do enough of this kind of thing with Josh last year? Do I do enough of this kind of thing in all of my English classes? I doubt it.

Ch 4 Real Rigor

On page 40 Tovani says:

I also need to remember what it feels like to read something for the first time. I can’t expect my students to be able to read and understand for the first time text that I work at over a period of time to understand.

I remember some years ago being asked, at short notice, to teach a Year 10 class for a term. They had just started to study Macbeth, a play that I hadn’t read. Each night I would anxiously and inefficiently read the scenes we were to read together the following day, trying to commit the notes in the margin to memory, trying to work out who was who and what had already happened, picking my way painfully through all the key passages. I was teaching other classes at the time, so I didn’t have the luxury of doing what I’d normally do when preparing to teach a major text: reading around it, watching a video or two, reading about it, thinking about how I might best approach the teaching of it. The train had left the station and I just had to sprint to get on board. At the end of the unit I breathed a huge sigh of relief, and said to myself that I’d be a happy man if I never saw a copy of Macbeth again. (In fact I ended up teaching it for several years after that, and came to love it, but only because I then had the time to get into it properly.)

This is how many students experience the play, I’m sure. They’re not given the time or the means to find their way through the challenges and into an experience of the drama and richness.

I worry that we’re repeating this mistake in this postgraduate course. The students are going to have 4 weeks (before they go out on a teaching round) to

- get their heads around the basic concepts of the unit,

- write an ongoing journal,

- select a student to interview,

- prepare a presentation and

- read Tovani’s book.

Of course all of these tasks are designed to help the students immerse themselves in the concepts, to raise questions and reflect on their experiences and assumptions … just as I’ve been doing in this journal. But I’ve been preparing myself for the past couple of months; they’re being expected to squeeze it all into four short weeks.

It isn’t fairfor me to spend days or even years planning instruction around a text, and then expect my students to read and understand concepts the first time through – especially knowing that reading comprehension drops when readers are reading unfamiliar information. (Tovani pp40-41)

The course won’t work if there’s no time for the students to think, to wonder, to explore side-tracks, to relate the course material to their own experiences, and so on.

Tovani Ch 5 ‘Why am I reading this?’

A chapter about purpose. A strong affirmation of what I was trying to say in an earlier blog post about ends and means: literacy is a means to another end, not an end in itself. We don’t read in order to read better or faster; we read in order to understand something better.

I must have a reason for reading the piece. There must be something in it that will make my life as a teacher or a person better. If the piece isn’t going to entertain, teach, or improve my life in some way, I throw it out. (p61)

It’s the job of the teacher, says Tovani, to make the purpose clear.

So why are we asking our postgraduate students to read Tovani’s book? I think there are three main reasons:

- To help them think about the unit’s central question: But I’m not an English teacher; is literacy really my business?

- To give preservice teachers practical suggestions from a practising classroom teacher on how to teach their subjects more successfully.

- To inform their thinking while they are doing the research project on an adolescent student’s reading.

I have to admit that I’m a tad uncomfortable with this. I’m a teacher who, at least most of the time, thinks “that setting the purpose limits the scope of the students’ reading’ (p60). I’m hoping that the students will have their own questions which they bring to their reading of Tovani’s book. I want to use our first tutorial together to surface some of these questions.

Ch 6 Holding thinking to remember and reuse

Lots of practical stuff in this chapter, different strategies for getting inside a challenging texts. It’s made me think about the strategies I use, and the ones I used to use. Tovani stresses active strategies; for her, underlining or highlighting is not enough. And, if I look back through what I’ve done with her book, there are quite a few scribbles in the margins when I’ve had questions or made connections.

But most of what I’ve done is to highlight, and then to write these little reflections. I think that’s always been the way I’ve ‘held my thinking’, or made it visible. By writing emails, or joining online discussions, or having conversations, or writing blog like reflections. I’ve always needed to feel that I’m communicating my questions and thoughts and summaries to someone else.

There’s another method I’ve used which I suspect Tovani might think was too passive (and too time-consuming). When I’ve been studying difficult texts, from the time I did my undergraduate degree all the way through to doing a PhD about eight years ago, I’ve copied out quotes. I like to hear, over and over, the voices of the authors I read, and somewhere on old outdated floppy disks I’ve got files full of quotes from Freud, Jung, Hillman, Nietzsche, Spinoza, Taylor, Bion, Campbell, Klein, Milner and others whose work I read for my PhD. And in a dusty plastic bucket in my store room, there are stacks of folders full of quotes (typed with an old ribbon typewriter, or handwritten) from the books I read as a young teacher, by John Holt, Dennison, Kohl, A.S. Neill, R.F. Mackenzie, and others. I love getting these out every now and then and hearing the voices of the authors who meant so much to me then.

But the world has speeded up and maybe today’s students don’t have time for that kind of slow absorbing.

I have a strategy I’ve come to rely (over-rely?) on in my classroom. I often ask my student to respond to two questions when they’re trying to get into a difficult text.

-

What do you notice?

-

What do you wonder?

These two questions seem to provide lots of opportunities for students to find ways into texts. I think they mirror the questions that good readers use naturally.

Tovani Ch 7 Group work that grows understanding

For lots of reasons, Tovani says, group work is an essential part of growing literacy. It’s a challenge establishing groups that discuss content well, but she’s sure it’s worth the effort.

I have such mixed feelings about this. On the one hand I hate being put into a group myself to discuss some issue that we’re not all properly prepared for and interested in; important issues get trivialized and nothing is achieved. On the other hand, I’ll willingly force myself through the challenges of a tough text if I know there’s a discussion looming with some respected colleagues. One of my greatest professional pleasures at my present school was a Professional Reading Group, where we’d all read the same book and then meet for dinner, wine and rollicking discussion.

Tovani herself talks about her struggles with group work. She was better at controlling and stimulating a whole class discussion than at facilitating productive group work. I’m the same. I love the cut-and-thrust of a good whole class discussion well managed, and at times feel a little rudderless when the groups are each going in their own unpredictable directions.

All of this Tovani acknowledges, and yet insists that it’s worth the effort. Norms need to be established, models and scaffolds provided and problems tackled. When it’s working well, it provides extra stimulation and motivation: reading is more purposeful.

Mmmmm.

Next term, as we act out various scenes in Romeo and Juliet, the boys will work in groups to read and make sense of quite difficult passages. Maybe I’ll use some of Tovani’s strategies.

Ch 8 Assessment that drives instruction

Tovani says to her students, “It will be hard for you to fail if you are willing to share your thinking.” (p102) She notes that “Meaning does not arrive. It is constructed over a period of time. (p104)”.

It’s so much easier if we can get students to share their thinking. That happens when we tie their grades to the effort they put into getting that thinking … into written form, and into class discussions. (p115)

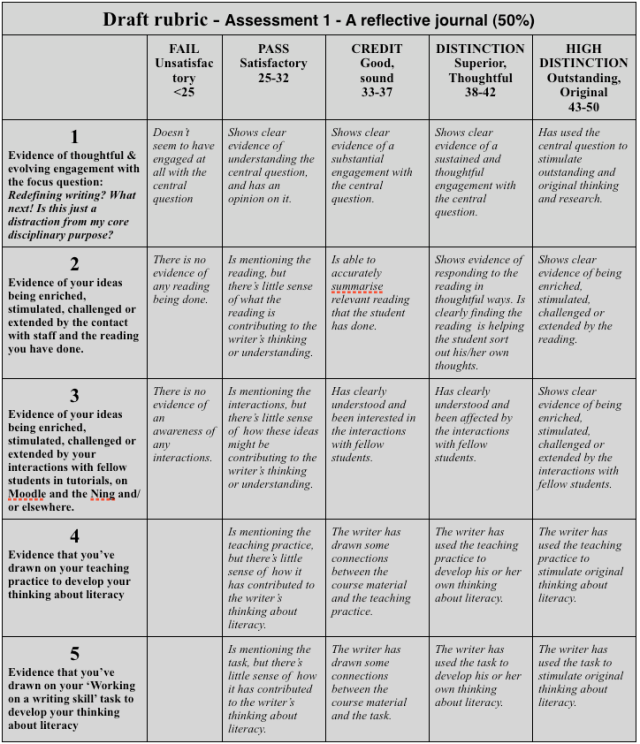

That’s what I’ve tried to do with this postgraduate Literacy Across the Curriculum course. The emphasis is on the students making their thinking visible, in sharing it and allowing it to deepen and evolve as the course progresses. Their grades are tied into ‘the effort they put into getting that thinking into written form’. They do not have to arrive at a particular conclusion or a pre-determined insight.

The focus question is: “But I’m not an English teacher: is literacy really my business?”, and any number of perspectives on this is possible. At one end of the spectrum will be those who want to define ‘reading’ and ‘writing’ in a particular way and assign the job to English teachers, or to primary teachers, or to homes. At the other end will those who think about literacy more broadly and see it as a part of their job as a teacher, no matter what their discipline. And there will be many other positions between.

The important thing is that the students reflect on their own experience, on the student they research, on the reading they do and the discussions (and lectures) they attend. So their journals are worth 70% and their research presentation 30%. These aren’t the only places where students will be sharing their thinking. We’ll be having tutorial and online discussions as well. I’m hoping that the students will draw on these in their journals and presentations … but the Tovani chapter does makes me think about whether we are assessing what we value in the best possible way.

Tovani Ch 9 Last thoughts

This is a great little book. I’ve loved reading it.

Each chapter begins with a story and the story that kicks off this chapter is a particularly moving (and encouraging one).

And it begins with a quote that I’d be pleased to have at the front of our postgraduate unit:

If teachers become distant from their own learning, they will most certainly become distant from the learning of their students. (Alisa Wills-Keely quoted on p117)

My year 11 Extension class is doing a course called ‘Text-Value-Culture’, and last term we read ‘The Odyssey’ and talked about the way this story has been appropriated by different writers for different purposes. This term each of the students has chosen a pre-WW2 text and a couple of appropriations to study.

My year 11 Extension class is doing a course called ‘Text-Value-Culture’, and last term we read ‘The Odyssey’ and talked about the way this story has been appropriated by different writers for different purposes. This term each of the students has chosen a pre-WW2 text and a couple of appropriations to study. My colleague at the university and in our course on ‘Literacy across the curriculum,

My colleague at the university and in our course on ‘Literacy across the curriculum,

At the wonderful

At the wonderful  As I walked away from the main groups round to a rocky headland, I saw a woman with a camera, pointing it at the sky behind me. After I’d passed her, I turned around to see what she was trying to capture. It was the last of the sunset. Brilliant orange and dark grey puffs of cloud against a pale blue sky. Like a Turner painting I saw once. It was exhilarating. I walked along the beach in the growing dark. In this mood, at this moment, after a couple of days of on my own with my own slow routines and with time to mull and to step back from the rush, things seemed connected and meaningful.

As I walked away from the main groups round to a rocky headland, I saw a woman with a camera, pointing it at the sky behind me. After I’d passed her, I turned around to see what she was trying to capture. It was the last of the sunset. Brilliant orange and dark grey puffs of cloud against a pale blue sky. Like a Turner painting I saw once. It was exhilarating. I walked along the beach in the growing dark. In this mood, at this moment, after a couple of days of on my own with my own slow routines and with time to mull and to step back from the rush, things seemed connected and meaningful.

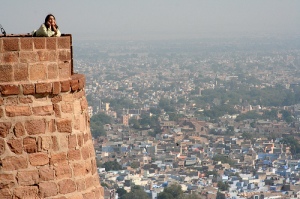

The image was of a walled city, Josh and his current known world on the inside and the rest of the world, represented in this case by Othello, on the outside. Josh is feeling hemmed in, wanting with a part of him to get outside the city, though in the grand scheme there are things he’d rather be doing than exploring Othello, which he assumes to be dated, lifeless and largely irrelevant to any of his deepest preoccupations.

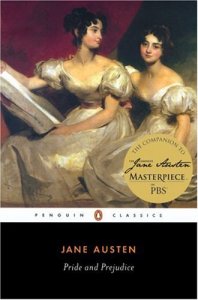

The image was of a walled city, Josh and his current known world on the inside and the rest of the world, represented in this case by Othello, on the outside. Josh is feeling hemmed in, wanting with a part of him to get outside the city, though in the grand scheme there are things he’d rather be doing than exploring Othello, which he assumes to be dated, lifeless and largely irrelevant to any of his deepest preoccupations.  I couldn’t stand Jane Austen when I was at school. Even doing an English unit at university couldn’t convince me that she was worth reading. Nothing of any consequence seemed to be happening in her novels, just rather meaningless social engagements, tame flirtations and inconsequential misunderstandings. Surely the world contained many more interesting things than these!

I couldn’t stand Jane Austen when I was at school. Even doing an English unit at university couldn’t convince me that she was worth reading. Nothing of any consequence seemed to be happening in her novels, just rather meaningless social engagements, tame flirtations and inconsequential misunderstandings. Surely the world contained many more interesting things than these!

As I read these blogs by Leonardo and Allen, I thought about the book I’m currently reading, Stanley Fish’s

As I read these blogs by Leonardo and Allen, I thought about the book I’m currently reading, Stanley Fish’s

In an earlier post (

In an earlier post (

A few days ago I was worrying about the

A few days ago I was worrying about the  Our AFL (Australian Football League) season has begun. We’ve had three rounds so far this season and my team, the Melbourne Demons, have lost all three games. By significant margins. Not for the first time, we’re near the bottom of the ladder. Some things don’t seem to change much.

Our AFL (Australian Football League) season has begun. We’ve had three rounds so far this season and my team, the Melbourne Demons, have lost all three games. By significant margins. Not for the first time, we’re near the bottom of the ladder. Some things don’t seem to change much. I copied my last post ‘Expectations, optimism and student performance’ over at the English Companion Ning, and

I copied my last post ‘Expectations, optimism and student performance’ over at the English Companion Ning, and  About an hour ago I was sitting with my 27 top set Year 10 English students. We’re studying satire, had just finished watching an Australian film called

About an hour ago I was sitting with my 27 top set Year 10 English students. We’re studying satire, had just finished watching an Australian film called

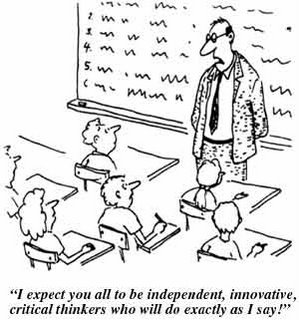

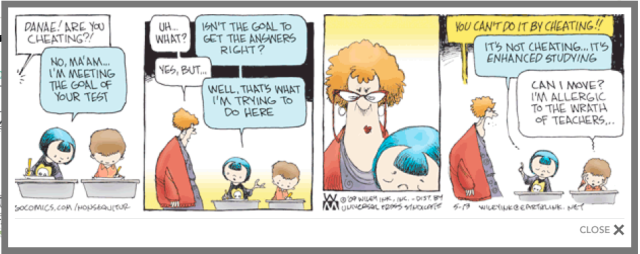

Our Year 10 satire course poses the question: ‘Should satire have an ethical intent?” It’s a bad question, I’ve come to realize, because it implies an option: that satire might have an ethical intent, or that it might not. I thought so myself, once. I used to think that there were two kinds of satire: the kind that just mocked for the sake of mocking, and the kind that was trying to achieve something worthwhile. Through teaching this unit for a couple of years (we come to understand more deeply through having to teach!), I now believe that true satire always has an ethical intent, that satirists are incensed or frustrated or dismayed or even concerned, and that they are motivated by a desire to expose some vice or folly that the rest of us might otherwise not see.

Our Year 10 satire course poses the question: ‘Should satire have an ethical intent?” It’s a bad question, I’ve come to realize, because it implies an option: that satire might have an ethical intent, or that it might not. I thought so myself, once. I used to think that there were two kinds of satire: the kind that just mocked for the sake of mocking, and the kind that was trying to achieve something worthwhile. Through teaching this unit for a couple of years (we come to understand more deeply through having to teach!), I now believe that true satire always has an ethical intent, that satirists are incensed or frustrated or dismayed or even concerned, and that they are motivated by a desire to expose some vice or folly that the rest of us might otherwise not see.